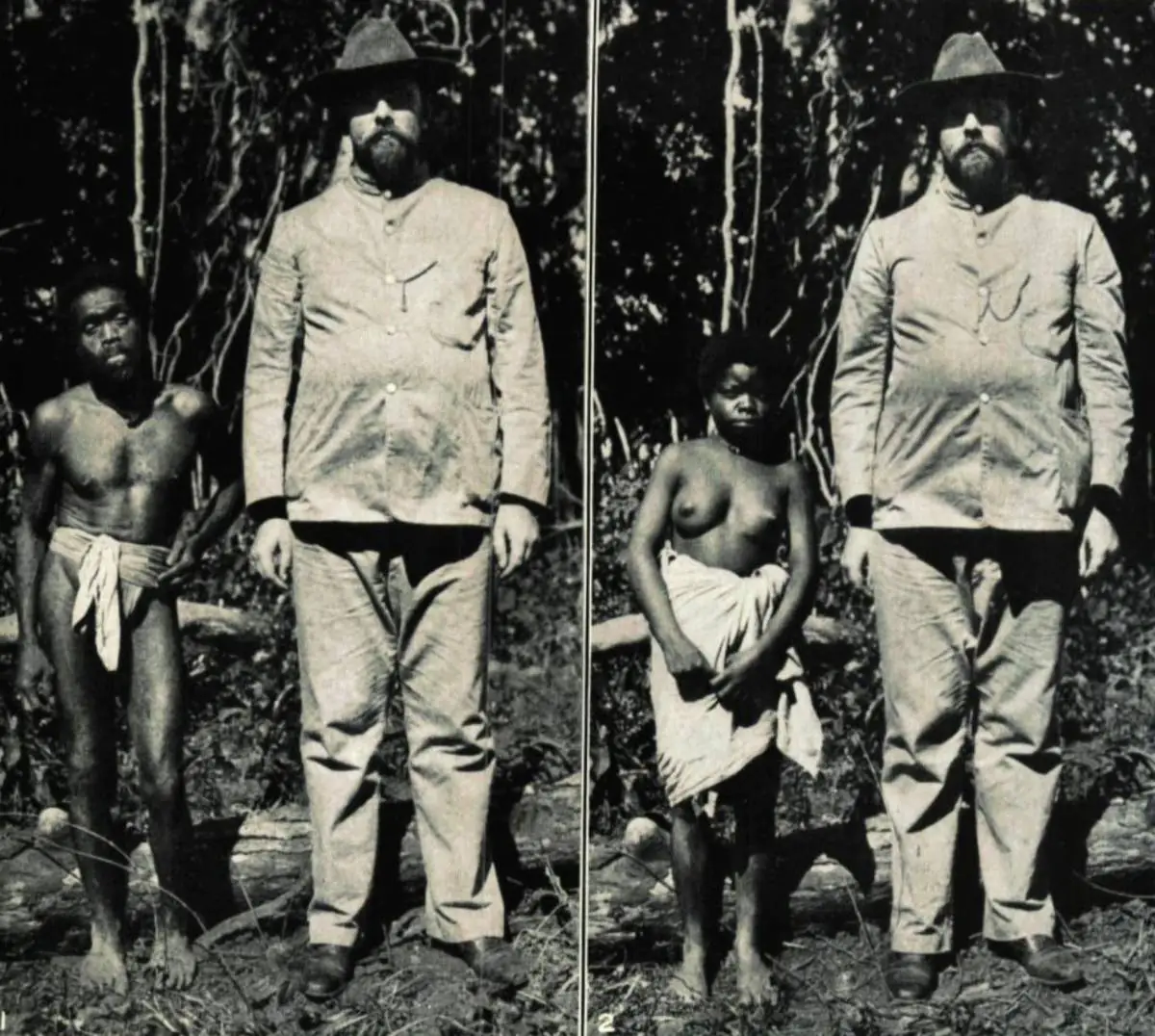

The Aeta, also known as Agta or Dumagat, are an indigenous people residing in various regions of Luzon, the largest island in the Philippines. As one of the oldest ethnic groups in the country, they are part of the larger Negrito group found throughout Southeast Asia. They share certain physical characteristics, such as darker skin tones, short stature, curly hair, and a higher frequency of lighter hair color compared to other Filipinos.

Historically, the Aeta are believed to have settled in the Philippines long before the arrival of the Austronesian-speaking people, with many researchers believing they were among the earliest inhabitants of the Philippine archipelago.

Traditionally, Aeta communities were nomadic, moving from place to place in search of food and shelter. Their intimate knowledge of the land allowed them to thrive in environments that others found challenging. They built temporary shelters from natural materials, relying on their deep understanding of local plants and animals for survival.

They organized themselves into small family groups of around one to five families. Each group was usually identified by their geographical location or the language they spoke. Despite being perceived as a single group, the Aeta are actually composed of various sub-groups, each with its own unique dialect and traditions.

The Aeta are known for their anarchic political structure, which is quite distinct from the more hierarchical systems found in other Filipino communities. They do not have designated chiefs or leaders who wield power over the group. Instead, decisions are made collectively, often with the guidance of elders known as pisen. However, these elders only provide advice and have no authoritative power to enforce decisions. This egalitarian system emphasizes mutual respect and consensus through deliberation, rather than control and domination.

In terms of gender roles, Aeta communities are also relatively egalitarian compared to many other societies. Both men and women participate in hunting and gathering, although women tend to use different tools and may hunt in groups with the aid of dogs. Women also play a significant role in their communities’ economic activities, often engaging in trade or working as temporary laborers in nearby lowland areas during the dry season.

One of the notable aspects of the Aeta people’s history is their resistance to external influences and changes. During the Spanish colonization of the Philippines, the Spaniards attempted to gather the indigenous populations into centralized communities known as reducciones or reservations. This strategy was meant to make it easier for the colonial authorities to govern and convert the indigenous people to Christianity.

However, the Aeta largely avoided these settlements, choosing to remain in the mountainous areas where the Spanish presence was less pronounced. Their resistance to such imposed changes allowed them to maintain their traditional ways of life for much longer than many other ethnic groups in the Philippines.

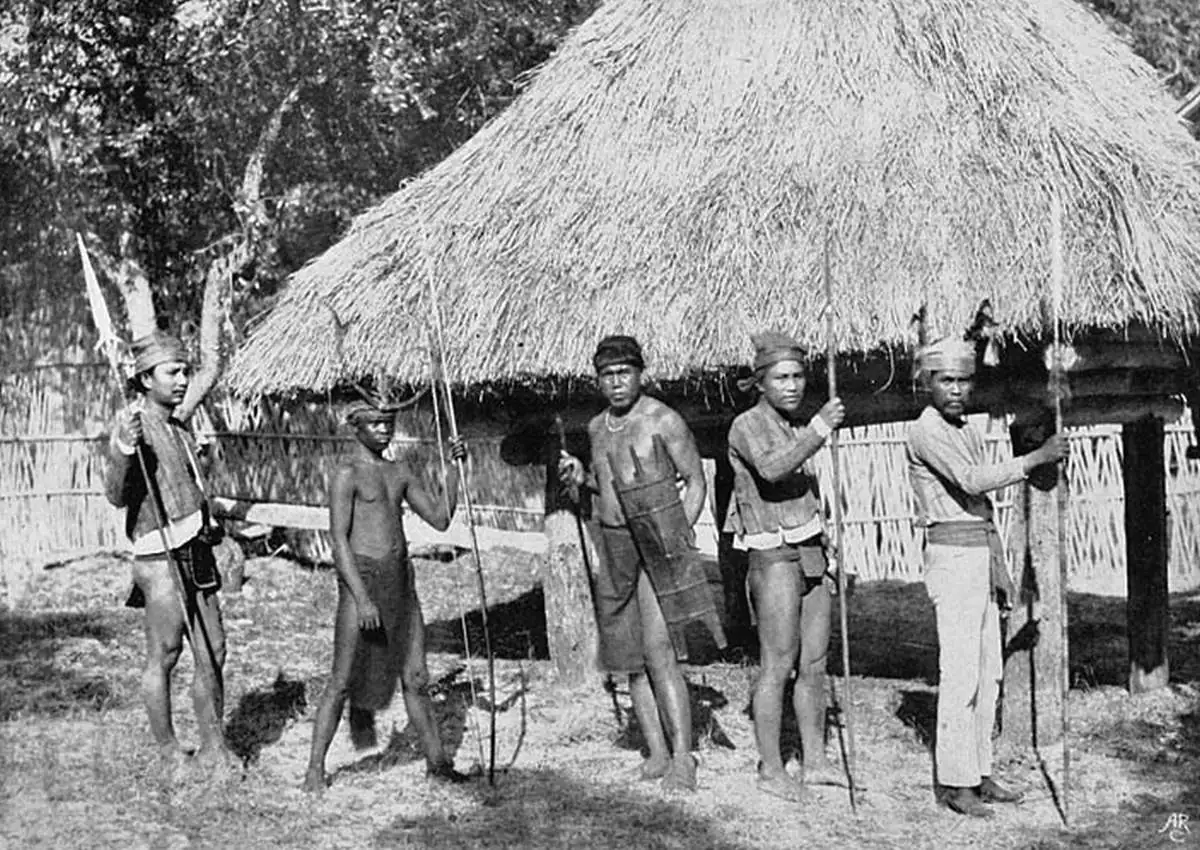

The Aeta’s traditional lifestyle has always been closely tied to their environment. As hunter-gatherers, they relied on their intimate knowledge of the forest, its flora, and fauna. They used this knowledge to hunt animals and gather food, often employing tools like bows and arrows, knives, and traps.

Their survival skills also extended to their ability to understand seasonal changes and the cycles of the tropical forest, which were crucial for their swidden agriculture, a form of slash-and-burn farming.

The Aeta are also skilled python hunters, using their weapons to defend themselves and hunt the snakes for food. But, being small in stature (Aeta adults reach about 1.4 metres or 4.5 feet in height), they are also potential prey for these massive snakes, which can grow over 7 meters long (the reticulated python is actually the world’s longest snake).

An 1976 study by Anthropologist Thomas Headland, who lived with a community of these hunter-gatherers in the Philippine rainforest, revealed that 26% of Aeta men have been attacked by pythons, and that despite their size disadvantage, they adeptly defend themselves using machetes and shotguns, with only six fatal incidents recorded over 39 years.

A 6.9 m reticulated python, shot by Kekek Aduanan, on the right, on June 9, 1970, Luzon, Philippines. Photo by J. Headland

Despite their long-standing resilience, the Aeta have been significantly impacted by modern developments and external pressures in recent decades. The eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991 was a devastating event for the Aeta communities living in its vicinity. Many were forced to relocate to resettlement areas, disrupting their traditional lifestyle. The influence of lowland Filipino culture and the encroachment of development projects have further contributed to the gradual erosion of their traditional ways.

As a result, many Aeta have moved to permanent settlements and have adopted more sedentary lifestyles. This shift has also brought about changes in their diet, health, and social structure. With the adoption of processed foods and other lowland practices, health issues like high blood pressure and diabetes, previously uncommon among the Aeta, have become more prevalent.

The political structure of the Aeta has also been influenced by their interactions with lowland Filipinos. While they traditionally resisted the imposition of hierarchical governance, contact with local officials has sometimes led to the establishment of community leaders such as a capitan (captain), conseyal (council), and policia (police). Despite these changes, the Aeta still largely adhere to their traditional practice of resolving disputes through deliberation, rather than punitive measures.

The loss of their ancestral lands is a particularly pressing issue for the Aeta. While Philippine law recognizes the rights of indigenous peoples to their traditional territories, in practice, many Aeta communities face difficulties in securing legal recognition of their land claims. Some have successfully obtained titles to their ancestral domains, but many more are still caught in a lengthy and complex bureaucratic process.

Despite these challenges, elements of traditional Aeta culture persist. Some communities continue to practice traditional crafts, such as weaving and the creation of tools and ornaments. Their knowledge of medicinal plants remains valued, with Aeta women in particular known for their expertise in herbal medicine. Some Aeta also work to keep alive traditional music and dance, important elements of their cultural heritage.

So, despite their resistance to external changes throughout the colonial period and beyond, the Aeta are now facing significant challenges as they navigate the pressures of the modern world. Their struggle to preserve their way of life in the face of encroachment and modernization reflects broader issues faced by indigenous peoples around the world. As they continue to fight for their rights and recognition, the Aeta’s story underscores the importance of protecting and valuing indigenous cultures and their knowledge.